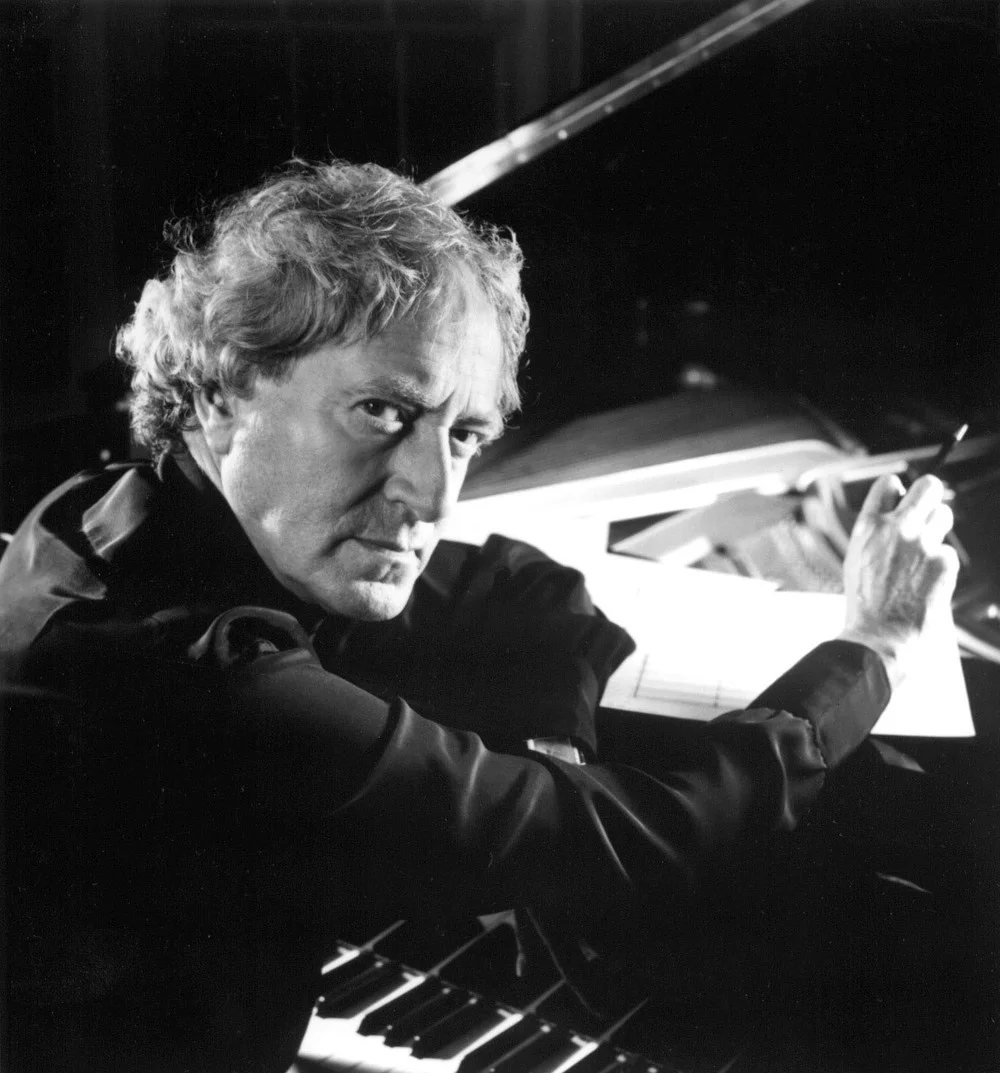

Rob Simonsen

Rob Simonsen is the evocative composer who has crafted diverse musical worlds for noteworthy films and television series including Tully, The Age of Adaline, Love, Simon, Nerve, The Upside, Father Figures, Gifted, Burnt, The Spectacular Now, Foxcatcher, Life in Pieces, and Seeking a Friend for the End of the World. Kickstarting his professional pursuits in film music, Rob apprenticed for composing legend, Mychael Danna, building his repertoire and command of storytelling on high profile projects including Life of Pi, Moneyball, and Fracture. After the success of their collaboration for 500 Days of Summer, Rob launched his solo career, musically shapeshifting between genres with confidence and refinement ever since. He is a founding member and creative director of The Echo Society, a Los Angeles based collective of musical innovators and artists. Most recently, Rob has signed a recording contract with Sony Music Masterworks with the intention of releasing his first solo album in 2019. In our engaging discussion, Rob speaks on returning to his jazz roots to accent the political scandal of Jason Reitman’s The Front Runner and the eclectic musical icons that have shaped his perspective as a creator.

Courtesy of Subject

Growing up in St. Louis, Missouri, what was your initial attraction to music making?

Well, I grew up in a fairly musical family. Music was around. There were pianos at my grandparents' and at my home, so I gravitated towards it. The piano was very much a reliable friend that was always there. I would always sit, emote, and have musical fun. As I got a little older, my parents encouraged me to take some lessons. My grandma was very helpful and instructive with that as well.

When I was about 13 or 14, I started getting into sequencing on synthesizers and using early MIDI programs on Macintosh computers on my own. I think that's where I got into bedroom producing, as it were. It just really went on from there. In college, I started playing in jazz fusion bands and continued to create my own stuff. I played in a little live drum and bass band and then discovered film scoring. There was no turning back after that point.

Can you tell us about some of your early experiences that helped define your identity as an artist?

I think it was playing my parents' records, picking out melodies on the piano from them. I was also listening to film scores and paying attention to music in film. I loved Vangelis, John Barry, and John Williams, of course. From a pretty young age, I also liked electronic music, symphonic music, and jazz. Once I started getting some piano instruction and discovered more about the world of jazz, that opened up a lot of doors.

In high school and college, I worked in record stores, which was great because I was exposed to thousands of different artists. A lot of the time, I’d get attracted because of an album cover, and that would lead me to find something that I wouldn’t have discovered on my own. I also talked to a lot of other people that worked there that could turn me on to stuff. That was a real big deal to me.

I think it was during the span of two years that I found Aphex Twin, Steve Reich, and Bjork. Those artists had some of the most significant impacts on me musically. They’re some of the brightest stars. They and Miles Davis.

What events led to a deeper exploration of film scoring?

Film scores were highly influential for me in terms of the music I was making on my own, working with synthesizers in my bedroom while I was growing up. In high school, I made friends with a group that was making movies in their spare time. During the summer and on weekends, we’d go and make films, then put music to them. In college, that group split up.

Everyone went their own ways and studied their specialty, and then we came back together and started making films together again, mostly student projects done after school. Another friend of mine scored one film, and he asked me to come in to play piano solos for the score. That was when the light bulb went off.

At that point, I never knew anyone in the business in any capacity. When I realized that this could be a viable career, I was totally in. There was no question. It just felt like I was built for it because it really suited my interests and my habits musically.

How did you come to work with Mychael Danna as an additional composer on high profile films including Moneyball, Fracture, and Life of Pi?

The first film that I scored went to Seattle International Film Festival, and Mychael Danna happened to be a guest speaker there that year. I loved what he had to say and liked his music. So, after he spoke, I got introduced to him, and we ended up spending a bit of time together during the festival. Serendipitously, we became friends and stayed in touch.

About a year later, I wrote to him asking him if he needed any help in Toronto, and he said, “No, but I’m moving to LA, and I will need help there." I was really excited. We ended up moving within days of each other, and a month after that, I started assisting him. He was very gracious to let me work up the ranks under him. It was amazing to learn so much from him and become friends. I’m just so grateful to have had the opportunity to spend time with him in that capacity.

What would you say was the breakthrough project that cemented your place in the industry?

Oh. Has that happened? To be honest, I’m not really clear about what that looks like. For me, I think The Spectacular Now felt like a creative arrival point. There have been all sorts of things along the way that I’ve been very proud of and worked very hard on, but how that appears to the world, I’m oblivious to that.

Was there a particular project you worked on that resulted in a lot more calls and interest in your skill set?

I think it was after 500 Days of Summer, which I co-scored with Mychael, that people realized I was a viable option. I got a lot of calls to do more scores in that vein. Often, film composers get more work after a score they’ve done is temped into other films and they are looking for something similar. A lot of my early work derived from those films and scores I worked on. That’s what led to me getting represented by an agency and securing opportunities of my own. A year or two after that, Mychael decided to move back to Toronto for some time. I moved my studio out from his and started working on my own with an assistant. I think that was really the departure point for my career.

The Front Runner is a dramatic retelling of former Colorado senator, Gary Hart's infamous reputation shattering scandal during the 1988 presidential race. What guided your decision to employ a vintage jazz-flavored treatment for The Front Runner? What aspects of this biographical narrative gave you the instincts to pursue this piano dominated stylistic path? Was there a reason you avoided an '80s tinged score?

It came out of conversations with Jason [Reitman, director, writer, and producer of The Front Runner]. Jason had a rule for the film — he didn't want any technology that felt like it was invented past the '70s, even though the film is set in the '80s. I think we did something very different. There are a couple of songs in the movie that are from the ‘80s, but that’s the only time that you're musically reminded of that period.

Stylistically, Jason was inspired by films from the ’70’s. We talked about different piano-based pieces and scores that we liked, and it just felt like an interesting take. After that, I just wanted to explore what the piano could do — not that it’s too experimental. There are plenty of scores and people making experimental piano music that push the boundaries much further, but I think, for me, I wanted to reference jazz piano without making it sound deliberately like jazz piano — maybe a cousin or relative of it. It seemed to work. There were times when I’d write a cue for a specific scene, and Jason would say, "No, didn't like it for that scene, but I love it in this scene.”

Things got moved around, but in the end, it feels like a nice cohesive score because you keep returning to the piano. I think it has an interesting vintage flavor. Even down to the mics and recording equipment we used, we really wanted to stay true to a sound that referenced the '50s, '60s, and ‘70s.

Did you happen record onto tape?

No, but there are tape emulations that I used to impart that kind of sound and character. I recorded with M 49s [Neumann]. They’re large-diaphragm condenser mics going through vintage Neve 1073s. They were made in the late 50’s — the same kind of mics used to record Kind of Blue. They have a sound that is just so indicative of that period. Very open and beautiful — I love them a lot. I used a few different mics, but those were the ones that ended up having the best character in terms of what we were trying to go for.

The Neves are just magical. I’ve never really heard anything quite like them. When you record through them, the sound is just there. It’s a sound that our ears are very used to from so many classic recordings. It has this slightly compressed sound, it adds warmth, it just helps things sit nicely. I feel very lucky to have them in my studio. I’ve just been pinching myself over being able to record through that stuff. Over the years, I’ve accumulated these very special pieces of gear, and even the piano itself is a special instrument.

I think when you're working with really simple elements, so much comes from the harmony, the relationship of the notes that you're playing together, or the sequence. I love it, and it’s also challenging. It is easier when you have an entire orchestra, and you have no limits. You can layer, and layer, and layer. For me, I’m increasingly more fascinated by fewer layers. When you have just two notes or limit yourself to a number of notes on a singular instrument, there’s an incredible tension that’s created. It was really fun to dive into that process and say, "How can I keep it interesting if we're gonna only use these very specific instruments?”.

Considering that you studied jazz piano intensively during college, were there particular musical references you revisited in advance or during the creation of your score for The Front Runner? How did you go about selecting the arsenal of musical devices you implemented?

I definitely revisited my Bill Evans records and listened to a lot of Dave Brubeck — Time Out. The film opens up with a Dave Brubeck cut. It starts with just upright bass, stomping and clapping, and then he comes in with this bluesy riff.

A lot of it was studying from a production standpoint. I was also listening to Kind of Blue, which is one of my favorite records of all time. All of those records were key for me. Some of the tracks I’m actually overdubbing on myself, playing a more percussive piano part and then doing more chord stuff with another layer. Bill Evans’ Conversations with Myself — I love that record. It's probably a bit more verbose musically than The Front Runner score, but I think a little bit is in there.

The instrument choices were really just born out of conversations with Jason. We found the palette of the film pretty quickly. It’s mostly just percussion and piano with a lot of other non-traditional instruments. The timpani shows up in a cue and acts as an underpinning bass line, but there’s no live bass. Percussionists were playing the drum kit, but I also added handclaps and sounds from slapping my legs and hitting my chest. I also played wire brushes on a book. It’s funny because I ended up playing on one of my Samuel Adler orchestration books. I tried others, but it just had the right sound.

Your first collaboration with director, Jason Reitman was for the comedy-drama film, Tully starring Charlize Theron and written by Diablo Cody. What would you say is the most inspiring aspect of working with Jason? How did your artistic visions intertwine for The Front Runner?

Jason is a writer, a director, and he’s also a musician himself. He is very good about knowing what he wants. In my two experiences with him, they've flowed really well, and we hit upon textures, instruments, voices, and ideas musically for both films pretty straightaway. I adore Jason, and I think that he's really smart. He’s got great ideas, and we have really satisfying intellectual conversations.

Jason has great powers of vision. He’s a very experienced director, and I think he has a good ethos with hiring people who he trusts. Without being too prescriptive about exactly what to do, he always knows how something should feel and when something is right. What more can you ask for?

That’s good fortune. In talks with other composers, it can often be a pretty nebulous process. How do you explain music that you both want, which hasn’t been created yet?

The most challenging part of any working relationship with a director is establishing a rapport with each other — a set of common understandings. When they say “purple,” I have to understand what that means. We have to share the same definition. You don’t always start off that way, and it takes time to establish. Sometimes, what you present can be not right at all. In those cases, you just calibrate, calibrate, calibrate and eventually, you get there. Sometimes, you get it right away.

I think a lot of times people just have a feeling, and they want that feeling to be hit. It is a fairly mysterious process to understand what that feeling should be and how to hit it in the right way. There's definitely craft involved in it, but look, if it were easy, we'd all be directors and composers. I just love the challenge, and I’m always up for it.

Tully pulled back the curtain on the realities of motherhood, offering meaningful perspectives on postpartum depression, how women view themselves after childbirth, and fizzling marriages. How did you come to grasp the mentality of Marlo? What experiments took place before settling into a reverb-drenched, textural atmosphere that used acoustic guitar to great effect?

It was really that Jason had a real solid vision for what he wanted — it was largely that. He had been using some of my other scores for his temp, so he wanted that sound he had fallen in love with. I understood what that was and created something new for Tully. He totally loved the very first piece I did, and it remained completely unchanged until the very end. That doesn’t always happen, but for that film, it did in a big way. Jason reassured me that it wouldn’t always be that easy, and I later found out after working with him on two films, that he doesn’t accept anything he doesn’t truly love. That made me very appreciative of how quickly we found the sound for Tully.

Love, Simon examines the life of a closeted gay teenager and his journey to self-acceptance within the frame of a romantic comedy. Your score makes delightful use of nostalgic '80's synths. What was the impression you wanted to leave on the audience with your music for Love, Simon and what was the greatest hurdle you overcame in executing this score?

I think we knew that we were intentionally making a bit of a love letter to John Hughes. For me, it was so great to use that warm nostalgia for a story about a kid coming out of the closet in high school. I think a lot of those films idolized that suburban life. They take place in those universes. I think it was such a clever and powerful concept for this film that has all those same feelings of nostalgia and safety. It was done in a way that represents other voices, and I thought they did a great job on the casting. It felt really diverse.

Thinking about what I wanted people to leave with, it was pretty simple, just warm feelings and smiles. We really had license to have fun, so I got excited when I knew that we were going to dive into that '80s world of things and turn the synths on. I grew up watching those movies, so I think that influence has found its way into a lot of my musical output in various ways.

I guess the greatest hurdle on the film was the final cue. We ended up using a piece of music I previously wrote that the director had in the temp. It was the final cue from Nerve, and he loved it so much. Despite my best efforts to write something original for the film, he ended up just really wanting to use that instead. The film ends with an ending cue from another movie I scored. In the end, it just feels like it’s coming from a similar world because Nerve also heavily drew on the ’80’s vibe. I have so much love for 80’s synth wave.

In your career as a composer, you have mastered the art of magnifying profound vulnerability in such a range of characters through your music — a tarnished politician, a struggling mother, a gay teen afraid to come out, a drug-addled rockstar chef, an immortal goddess. What are your strategies to get to know a story and determine the musical world that belongs to it?

I'm always trying to listen to my inner ear, in terms of what it might be wanting to hear from a film. The first time I see a film, and I'm watching it without any other music, I let my eyes soften, I let my ears soften, and I just pay attention to hearing something. I don’t exactly know how to explain it, but I look for ideas and inspiration. My brain connects the dots to all the things I’ve heard before that it might recall through association. I'm not really sure exactly where it all comes from, but I think it was Philip Glass that said, "Writing is about listening." I really believe that. I'm always trying to have a sensitivity to what I would want if I was the one sitting in the theater and watching it.

There are all sorts of things that you might not go with because you already know they might not be the appropriate thing musically. It begins with the ability to have a vision for something. Sometimes, my vision is totally wrong, or I’m the only one who thinks it’s great. I believe to be able to dream up something that speaks to the heart of a character, or for the situation, or for an element of the situation that we do not see on screen — that’s what makes really good film scoring. I learned a lot about that from Mychael Danna too.

Which character from all the films you've scored resonates with you the most personally and why?

That's a tough question. I keep thinking about The Way, Way Back. I remember what it felt like to be a young teenager going through puberty. You know, feeling awkward, meeting a girl on a summer vacation that I thought was really cute, dealing with family drama, and finding that older cool guy idol to become friends with, who teaches you things about life. I just really felt like I understood that character pretty well from my past.

There's also a scene in 500 Days of Summer where he [the character of Tom played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt] looks in the reflection of a car window, at his own reflection, but it's actually Han Solo winking at him. He had a triumph with Summer, and I just really, really related to that moment. Growing up, Han Solo was such a symbol of the cool guy that other guys want to be like — the bad boy, good guy.

As a co-founder and creative director of the Echo Society, what has been the most positive and artistically invigorating addition to your life since you launched the collective? What would you say is the dictum that underpins your activities?

It’s been amazing to be a part of a group of friends that are all pushing each other to collectively birth something that excites us all. The ethos is to try to do things that we haven't done before, that we might not get a chance to do in our commissioned work. There have been countless things that have been amazing on an artistic level — just having the opportunity to write music that is only going to be performed for people in a live setting, facing that challenge on a personal level, and seeing the enjoyment everyone has in collaborating with each other and sharing it with an audience.

We've sold out pretty much every show that we put on. That, to me, is an excellent indicator that people are into what we're doing. The excitement that comes from just exploring what’s possible is a little contagious. We’ve been impacted by seeing other people jump in and create things. I also think it’s helping to create a climate of experimentation in Los Angeles. It’s a great artistic time for the city, and there are a lot of exciting things going on. People are taking the reins of what they want to create. It’s been happening in both Europe and New York for a long time. The entertainment industry dominates L.A. It's too easy for people to be sucked into their studios, focused on the work life. The Echo Society has really felt like this blossoming of making art for art’s sake.

I think it’s connected me to a lot of other great artists in the community that I might not have had a chance to get to know or even be exposed to. I am really excited about that and grateful that we’ve been able to continue for this long. We have a lot of plans for the future as well.

In addition to your talents as a musician, you are also a gifted graphic artist, showcasing your visually addictive works on Instagram. Can you tell us about how this pursuit began?

Most of the time, I'll start with a photo that I've taken, and then a lot of it is just manipulating and adding things with apps on my phone. I don't really use Photoshop. The more traditional photography is taken on a digital SLR, which I love as well.

For me, photography and visual arts, they share these really lovely connections with music, but it's something that can be done so quickly, and then it's finished. It’s a lot quicker than making a piece of music. There's a strong tie between music and imagery, and maybe that’s why I've gravitated towards the film scoring world. I think I've always had a lot of imagery happening in my head from listening to music, and it works the other way as well. When capturing an image, there's a certain tonal quality or a certain feeling that I'm trying to go for.

My goal has always been to travel the world and make music, so if I'm not making music, I'm usually traveling. Sometimes, I'm doing both. I did my whole record in Paris and have made music in different cities. But the camera, like the piano, it just feels like a companion, a friend. I love chasing sunsets, sunrises, vistas, and moments.

Considering that your art harnesses beauty in the natural world, what are the most breathtaking places you have visited and incorporated into your work?

I would say that Japan and Iceland are the places I’ve found to be the most stunning and jaw-dropping. I love nature deeply. I think some of the most powerfully inspiring moments I've had in my life have been out in nature, seeing stars in the sky, a beautiful sunrise, or a sunset. There have been moments that I've felt overwhelmed by the beauty in nature, so I really chase that. Growing up, I spent time in Colorado and the Pacific Northwest, which have some amazingly beautiful places as well.

If you could magically adopt the talents of different music luminaries overnight, which would you choose and why?

The flowing enchanting nature of Debussy. The simultaneously alien and familiar experimentalism of Aphex Twin. The unexpected inventiveness of Prokofiev. The hooky, grooving, funky nature of Quincy Jones. The organic sensibility of Bjork’s electronic production. The evolving sonic tapestries of Steve Reich.

Interviewer | Paul Goldowitz

Research, Editing, Copy, Layout | Ruby Gartenberg

Extending gratitude to Rob Simonsen and White Bear PR.