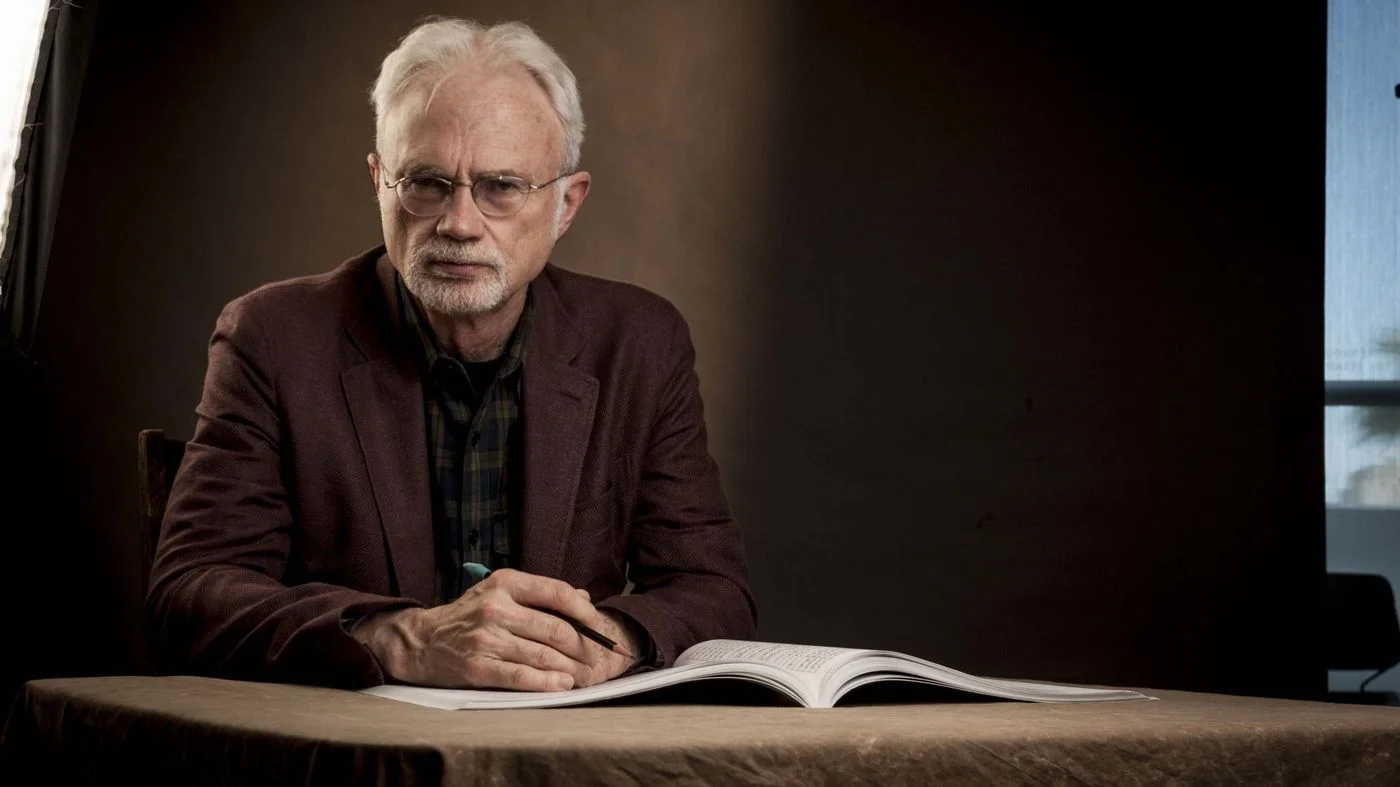

Mark Isham

Mark Isham is an iconic Emmy and Grammy-winning composer, electronic music wizard, and jazz luminary. Ever since his breakout score for Caroll Ballard's Never Cry Wolf in 1983, Mark has crafted tantalizing music worlds for high profile films and television shows including Crash, Once Upon A Time, Blade, The Black Dahlia, The Accountant, Nell, Black Mirror, Beyond The Lights, Philip K Dick's Electric Dreams, Marvel's Cloak & Dagger, and A River Runs Through It, for which he was Oscar-nominated. As a recording artist and performing musician, Mark has exercised versatility and demonstrated sublime musicianship in his prolific body of work, collaborating with the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Willie Nelson, Van Morrison, Joni Mitchell, and The Rolling Stones. In our focused discussion, Mark speaks on the evolution of his gorgeous Emmy nominated orchestral score for the final season of Once Upon A Time and honors his greatest influences.

Source: Mark Isham

Congratulations on your Emmy nomination for Once Upon A Time. You have been composing for the series since 2011. From your perspective, how has your approach to the score evolved over time? What about writing for this far-ranging fantasy world allows you to stretch your own artistry?

I think we’ve gotten better. The approach actually has not changed musically. One of the things I’m most proud of is that I had this idea of what to do and how to do it, and it just works. It worked from the pilot and we haven’t really had to change anything.

The evolution is not conceptual. It is simply in the material itself and revolves around the addition of characters. Every time they would add a character or a relationship, we would work with that and add new ideas. We’ve done over a hundred themes because there have been hundreds of characters and relationships. Rumple has a theme, Belle has a theme, their relationship has a theme, their relationship going on the rocks has a theme.

It’s just a lot of organization in a way that I normally don’t do these sorts of things. I’m usually not so theme oriented. So, to make sure that if Hook enters the scene that we pay a little tribute to that thematically, was fun and sort of a new way of doing things for me. The eight-minute pieces contain three or four main themes that we get throughout the entire seven years.

Again, one of my proudest accomplishments is that the material was generated for a pilot. For pilots, you don’t usually have that much time to think. You just do your best work and you hope for the best, yet the things we generated for the pilot have held up for seven years.

Adam and Eddie [Horowitz and Kitsis, creators of Once Upon A Time] are inspiring. Their love of the material, and the way they present the material. I fell in love with it and it just continued to inspire.

The score of Once Upon A Time is deeply orchestral, predominantly implementing organic instrumentation. In your opinion, what about the series lends itself to this type of musical treatment? Can you walk us through the sonic palette you deployed this last season?

I think that the palette develops because of the characters. As I said, every character having their own theme is very traditional, but these are not only traditional characters, they are iconic. You know, every child grows up with some form of these characters. So, it felt like it had to be presented in that time-tested style of orchestral thematic film music writing.

The last season, even though we got a little more into contemporary life in Seattle, we decided not to really change it too much. There's a little bit of contemporary influence. I remember for the flashbacks to Emma living in Seattle, we had a slight contemporary influence in the score, but we never really wanted to pull it too far out of the original concept. because even though Regina’s running a bar in Seattle, she's still the queen. The music is there to help you remember the duality. By the time, we're into the seventh season there are four or five layers here of where everybody's existing.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, you provided an engaging electronic score for Marvel’s Cloak & Dagger, which examines the unlikely romance between two young people who develop superpowers. What themes within the narrative did you intend to highlight with your score?

Cloak & Dagger is very much a teen coming of age story. It’s just heightened, of course, by the fact that these particular teenagers are accruing these mysterious superpowers. So, I wanted to keep the vocabulary much more tied to the type of songs that are in the show, so you would feel one vocabulary for the music overall. There is a slightly contemporary pop influence to this score, but at the same time, it’s very edgy electronica, which seems to fit with the nature of the storytelling.

There is a compelling interplay between the licensed material and your music. Was that a conscious decision from the very beginning?

Oh, yes. In my very first meeting with Joe and Gina [Pokaski, creator and Prince-Bythewood, executive producer of Cloak & Dagger], when we worked on the pilot, it was Joe that said, “Look, I'm really going to be using songs to help establish the time, place, and everything for these kids. I really would love you to be working within that.” In fact, there have been times when we've overlapped and had score going on top of intros to songs. We've discussed even trying to get remixes of parts of the score of the songs more intertwined as we keep going.

You scored the Arkangel episode of Black Mirror, which follows a single mother’s ethical dilemma and the damaging consequences of censoring her daughter’s experience of life through a neural microchip implant. What was your initial inspiration for the episode?

Well, Jodie wanted the music to be able to reflect the normalcy of their life from the beginning, and then on a dime, just be able to turn into this really psychotic inner world. Even from the very beginning, we're allowed to sense that this mother lives a bit mentally on edge, that she's very well-meaning, adores her daughter, but is pushed a little to the limits of overprotectiveness. So, we have a sense of imbalance even from the very opening few scenes.

The score basically heightens this juxtaposition of what should be normal life with this heightening desperation, and eventually, the psychotic breaks that occur. The intention was to hint at something like, “This should be normal, but maybe not”.

You’ve collaborated with Jodie Foster in the past. How was this opportunity different for you?

Creatively, it was not different at all. We've always gotten along very, very well. She’s a very accomplished director. I've scored several films she's acted in and then, obviously, scored several of the films that she has directed. We understand each other and communicate very, very well. She is just one of the smartest people I've ever met and is a joy to work with.

As you know, television has different parameters of production, timelines, and things like that, but we’re both very professional, we figured it out and I think we got a very high-quality product.

You are a classically trained trumpeter, have mastered the world of jazz, and possess rich expertise in synthesizers. Who were the musical luminaries that had a profound influence on you from an early age?

When I was young and playing in the symphonies, I really enjoyed player Mahler and things like that. I studied some of the great composers at the turn of the century and the 20th century. Samuel Barber is another one. And then, of course, the minimalist, John Adams, Steve Reich. I would say John Adams is probably my most current influence as an orchestral composer.

Growing up, I discovered Miles Davis, and he really changed my whole point of view on improvisation, the sound of the horn, and what you can do in the jazz medium, and minimalism in terms of writing and composition in a melodic style. And then, Brian Eno was a huge influence as a producer, sound designer, and conceptualist. His work from David Bowie all the way down to The Talking Heads. I loved all that stuff, as well as his ambient work. He had a whole series of ambient records, but he really founded that whole genre back in the '70s.

And then I think the other main influence for me, and especially in the jazz world, was the band called Weather Report. They convinced me that you could have world music, jazz music, and classical music, and they could simultaneously influence each other and create a profound musical impact. Even though none of the music I write really sounds like Weather Report, the idea they instigated of having a fusion of genres still made a huge impact and offered inspiration to me.

What are the core differences between your scoring work and the music you make as an artist, for example, your vinyl release last year? What opportunities for self-expression do these distinct mediums present?

That particular vinyl release was my take on covering standards as a jazz trumpet player. You know, it's a time-honored tradition that jazz players reinterpret standards and I just wanted to take a new pass at that concept as of 2017. So, I put my remix DJ hat on and built these tracks, and then I hired myself as a trumpet player to come in and play on top of them. It’s fun. I tried to really push the envelope a bit in how one might reinterpret some of these songs.

There's a Duke Ellington song on there, there's this Antonio Carlos Jobim song, there's a Marvin Gaye song. I mean, there are the classics that so many different generations of people have grown up on.

When you commit to a new project, can you elaborate on the first steps you take to write a theme or establish an aesthetic? Do you have any rituals or habits that condition your creative process?

Most of the work I do starts on the computer, although probably the first decision I make comes from asking myself, “Is this going to be a very traditional piece?”. In which case, I might come up with an 8 bar, 16 bar theme, maybe two or three different 8 bar themes, 16 bar themes for a project. Sometimes, I start at the piano and not even worry about computers or sounds for a little bit, focusing on creating really well-constructed themes that emotionally tell the right story.

That’s one approach, but more often than not, in this day and age, it starts with just picking sounds that are going to reflect the atmosphere of the show and the sound of it. If it’s a show that has melody, even though it’s electronic, then what might those melodic instruments be? A lot of projects these days don’t even want a strong melodic sense, it’s much more about the atmosphere and the texture, the ambience of it.

It’s like an artist going and picking their colors, you know? Am I going to work in blues and greens? Am I going to work in blacks and reds? It's those sort of choices. I'll spend as long as a week sometimes, just watching scenes, playing a note here and there, and just seeing what happens like, “Ooh, that sound really connects with that, and these sounds don't, so we'll get rid of those”. That’s how you build up a palette.

I build up my templates, and then along the way, ideas will presumably start flashing in front of me and I very quickly try to get them down. I don't necessarily worry about making them fit the picture or how long or short they are. If there's a good kernel of an idea, you just want to get it down. I’ll end up with maybe 20 different ideas all sketched out as a starting place.

Compositionally, I work in Logic. Sometimes, if I have been working too quickly or I’m lazy and I’ve got the wrong tempo in there, I’ll go back, do the math, and figure out how to get the right tempo, but the main idea is to get those ideas down as they come, so you can keep the creative juices flowing.

Throughout your decorated career, you have been continually applauded for your prolific nature, strong work ethic, and versatility. What are the essential skills and traits that a composer should cultivate in order to enjoy a long career and remain relevant as you have?

Oh, my goodness. Well, I think you just stay aware of where the trends in music are going, and how your personal sound interacts with that. I figure that people want me to be me, and that's why they hire me because there's something about me that they’re responding to. I never want to lose that, but at the same time, it’s important to keep oneself relevant and aware of current trends in art and filmmaking. You still have your own voice. That’s the reason I still love what I do. Every project invites an entire learning experience of something new. I think it's the fundamental joy of life is to know more and more about it and have richer and richer experiences.

Interviewer | Paul Goldowitz

Research, Editing, Copy, Layout | Ruby Gartenberg

Extending gratitude to Mark Isham and Costa Communications.