Marcelo Zarvos

Marcelo Zarvos is the intrepid Emmy-nominated composer who has executed stunning and vivid musical atmospheres for a plethora of exalting films and television series, such as Ray Donovan, The Affair, The Best of Enemies, Wonder, Fences, What’s My Name: Muhammad Ali, Sin Nombre, Brooklyn’s Finest, The Romanoffs, The Chaperone, The Good Shepherd, Enough Said, Breakthrough, Tully, Phil Spector, The Door in the Floor, and Mapplethorpe. Since establishing himself as a hot commodity in the New York independent film scene in the early 2000s, Marcelo has attained mastery of blending drama and mystique, exhibiting tremendous range, a taste for life, and clarity of artistic vision for each narrative he supports. From ethereal piano performances to cavernous electronic soundscapes to mesmerizing jazz-infused arrangements to Latin romanticism, Marcelo’s emotionally involved approach to film music invites the opportunity to explore the subconscious mind. In our entertaining discussion, Marcelo reveals why scoring for media is well-matched for his musical eclecticism and leads us on an adventure through the broad spectrum of projects he has fulfilled in a season of creative abundance.

Source: Chris Frawley

Hailing from the rich cultural context of São Paulo, Brazil, which musicians and icons formed the basis of your artistry?

You know, I would say a healthy dose of The Beatles. Even though I was born the year they disbanded, they were very, very important to me — that’s how I fell in love listening to music. Not to be controversial, but I feel like you can hear their influence in almost all of the pop music that followed and trace it back, with the exception of hip-hop. The richness of the songwriting — there was something special about it that impacted so many musicians, so many composers that came after. After becoming a father myself, I’ve played their music to my kids after all this time, and they love it. [The Beatles] really capture the imagination of everybody. The music cuts through everything, and they probably couldn’t even tell us why themselves, but it’s just one of those things that happen in art. When the chemistry works and all these different elements come together to create something greater than the sum of its parts — I certainly feel that’s how the Beatles were.

I was also into scores from the 70s and 80s — a lot of electronic stuff like Tangerine Dream. Vangelis was a big one I really loved — Bladerunner and of course, Chariots of Fire. I listened to a lot of ’80s pop music and bands from that time. I would say those were the first influences. When I was a teenager, I started getting into jazz. There were a number of artists from the ’70s and ’80s whose music I enjoyed like Keith Jarrett and Pat Metheny. I was very into minimalist composers like Steve Reich and Philip Glass. Then there was a lot of Brazilian pop music, particularly from the ’60s and ’70s, and bossa nova. Most of all, Brazil’s greatest composer, Antônio Carlos Jobim, was a pretty significant influence on my work.

What events led to you to engage in courses of study — film scoring at Berklee College of Music and 20th-century classical music, world music, and experimental jazz at CalArts, and pursue a career in composing?

You know, when I came out as an eighteen-year-old in 1988, I wanted to study film scoring, and I went to Berklee with the intention of doing that. When I got there, all of a sudden, it dawned on me that maybe it was a little early for me to be so focused on film scoring. I sort of had an epiphany and felt that I should really learn all about music first. I had been playing music and performing as a musician since I was eleven, but I wanted to train more before becoming a film composer. I was very interested in those styles you mentioned, so CalArts ended up being the perfect place for me to do that. There, I was exposed to so many styles of music and cutting edge perspectives in all these different genres, and I spent a lot of time exploring. In the back of my mind, I knew that film scoring was where I eventually wanted to land because I had been a cinephile as a kid, watching as much as I could and I really remembered everything I saw. But it was not until ’98, long after being out of school, that I actually had my first experience of scoring a film.

One of my main attractions to film very early on, was the music. I realized later that a big part of that was how musical styles were mixed in a very natural way. When I was making my own music outside of film, drawing from a little bit of classical, a little bit of jazz, and a little bit of world music, people would always ask me, “So, what is it? Which one of these things is really you?” In film, television, music for media, nobody has ever asked me that question. Not only do they not ask these questions, but they almost expect you to experiment and combine all these elements into your scores. That remains to be a very attractive aspect of what I do. I can do an orchestral score with crazy world percussion, or mix electronic and jazz without a problem.

I think part of the reason this can be done has to do with the people on the receiving end of a film or a TV show. Depending on the project, you will have any number of songs on top of a score, and they are just taking in all of this information that’s coming at them without questioning. They’re just being affected by the music without asking what it is. What matters most is how it hits you emotionally. That’s still what excites me so much about film scoring — the idea that people can be somewhat disarmed by the fact that they’re watching a story, and the music is a guide. It’s a cliché to say, “Wow, a great film score is one you don’t notice.” And that’s a controversial statement. I think it’s the truth sometimes, and not true other times, but nevertheless, there is an element of acceptance when you’re sitting there and watching a story unfold, not choosing what comes to you musically, but just immersed in the sound. That whole exchange, that interaction has always been very, very interesting to me.

The Affair explores the psychological effects and emotional ramifications of an extramarital love affair that destroyed two marriages. Your textural and evocative piano rich soundscapes cast a mysterious shadow over the entire series, exercising incredible restraint. In season four, the series reaches its dramatic climax when Noah and Cole identify Alison’s body together. Considering that her death definitively alters the identity of the series, what did you intend to achieve musically in this episode? Please describe the sonic elements that you assigned to the character of Alison.

The Affair is all about creating an emotional reaction for the viewer. Sometimes it’s just getting out of the way of an emotional reaction, and creating ambiance. The episode you’re talking about is less dialogue heavy than usual, so the music comes through more. It’s been a great lesson for me to navigate this deeply emotional material. Of course, this is the episode where Alison dies, but from the beginning of the series, you learn about Gabriel, Alison’s dead son. There have always been very, very dark things happening onscreen, and how to approach them musically has been a real challenge.

Seeing Alison’s body is a very crucial moment in the life of the show. When one of the protagonists dies, it becomes very loaded emotionally for everybody within the story, and for all of us craftspeople who are working to tell the story. The piano was a big part of Alison’s sound, as well as electronics and sometimes, voices performing wordless singing. In the end, it’s a big mix of sounds and guitars, but there is always an ethereal and otherworldly quality about Alison. During the series, she talks about just trying to make it to [the age of] 35. She’s a very disturbed character and somebody who never really recovered from a trauma that is so horrifying that it’s understandable. Even so, she had this magic quality that made it so the two men never really got over her. It’s a double punch in the gut for Cole because he was about to tell her he wanted to get back together with her. And Noah, I think the happiest moments of his life were with her. The whole show and all the characters feel a little lost without her.

For me, Alison is, in many ways, the heart of the show, certainly musically and emotionally because of the depth of her sorrow. Her sexuality is also a big part of the story and her identity. This event was a real emotional climax for The Affair, but also something very difficult to get over creatively. It was tough to continue to explore the story after she was gone. Her character remains almost like an invisible presence for the rest of the season. Even in the final season, her presence is still felt because her actions changed the course of all these peoples’ lives. That’s essentially how the series ends — everyone finally finding themselves again.

Historically, which scenes in The Affair have you felt most proud of?

You know, in season two, the night of the accident — I found that very interesting to score. Like all things in The Affair, you see two points of view of what happened, so that was a big moment for me. Some of the things you hear in season one with Alison just talking on her own, even as far back as the pilot, those themes remain very strongly in the whole arc of the show. When you write themes for a pilot, you never know if they’ll stay there for a long time, or it’ll just be that one time, but these ones have lasted.

In season three, Noah’s psychotic break was a very fun thing to score. It was treated almost like a horror movie at a certain point. Season three was basically psychological horror, so it forced me into a much more dissonant and anguished sound. In season four, I think it was all about the openness of being in California — finding a new beginning for these characters and their sounds. I was very happy with how it ended up being portrayed.

The final fifth season of The Affair will alternate between a present-day storyline revolving around Noah, Helen, and their four children, and an adult Joanie Lockhart decades into the future, searching for the truth of her mother’s demise. Are there any hints you can give us about how you will musically illustrate this dramatic send-off?

I’m right at the beginning of it. Because there’s a big jump in time for a portion of the story, I’m focused on finding the music for the distant future, which has been interesting. We see Alison’s daughter all grown up about thirty years into the future, and we learn what’s become of planet earth. It’s a little bleak.

I’m also trying to find something at the heart of these new characters, and find shades of Alison’s music within it. They just wrapped up shooting, so we’re just starting to get into post [production] now. I don’t know exactly where we’re going to land yet, but we’re finding the tone of one last adventure with this band of misfits.

Ray Donovan is a crime drama revolving around a professional fixer with a sordid past, who cleans up the messes of power players and glitterati in Los Angeles, and later, New York City. The series is something of a taboo-breaking exercise, exploring traumatic family affairs and madcap situational comedy within an ultraviolent frame. This mayhem is all supported by your stylized electronic dominated score. What are the most evident ways that this tumultuous narrative has challenged you as an artist?

In the case of Ray Donovan, one of the big things has been how to capture Ray himself with music. He’s such a stoic, quiet character. He doesn’t say a lot with words, and he does a lot with actions. We wanted to create a sound that would give him emotional support but wouldn’t soften his journey or persona. He’s a really, really tough person, who takes everything you’ve got and keeps going.

We really held back musically for almost half of this season until Ray gets going again because there’s a lot of grief surrounding the loss of his wife, Abby from the previous season. In a similar way to what I was talking about Alison being gone from The Affair, I think Abby is still hovering over Ray Donovan. Ray really misses her, and we even use that in the music of certain episodes in this sixth season to point out that he continues to think about her and remain very much in love with her. And it’s also been about showing the complexity of his family. They’re all very flawed people, but they ultimately gravitate towards love and each other. It took time to figure out how to support the drama and the emotion without taking away the toughness, and also the fun.

Another big challenge was figuring out how to portray New York City as a new prominent character in the story. All of a sudden, Ray is out of his comfort zone in this new place, and it’s not until the end of the season that he finds his place — as much of a place as someone like Ray Donovan can find. Something about being in New York needed a darker, grittier palette. Overall, we were looking to do a contemporary noir score without resorting to an actual jazz sound. We just wanted that spirit and darkness that noir has, but in a modern setting. Figuring out how to do that without becoming a cliché was difficult. We didn’t want it to be like, ‘Here’s New York. Here comes the jazz’. We even tried some jazz at one point, but it never felt right, so we created our own version of smoky bar music but true to today’s world.

What specific instrumentation did you deploy to create this atmosphere?

A lot of it is made up of various instruments that are manipulated after they are recorded, and there are some custom instruments we use throughout. We worked with this instrument called the pencilina [an electronic board zither]; there’s a person in New York that built it and plays it. There are also a lot of prepared guitar sounds, where we put things on the guitar strings to make it into more of a percussive instrument. We did a lot of that, and used many heavily, heavily processed sounds. Even when we used pianos, they would be run through a lot of distortion and effects to become their own thing — transcending the sound of the original instrument. There’s almost a claustrophobic feeling to the music. It’s a little bit oppressive to reflect what Ray is going through. Some of the tracks tend to be very thick and have a lot of sonic range, which creates a certain sense of doom for Ray and where he’s headed.

This season, we also had a violence theme which is shared by all the Donovans. We used it for Terry’s bare-knuckle fighting, and when Ray gets into fights, and for Mickey’s crazy antics. I found myself gravitating towards a lot of distortion because there’s a lot of anger and anguish in that sound.

In the penultimate episode of the sixth season, ‘Never Gonna Give You Up,’ we witness Ray, along with Daryll and Mickey, embark on a rage-fueled night hunt for Ray’s daughter, Bridget, which is only further intensified by his wife’s recent death. What were the initial musical concepts you explored to convey the severity of these circumstances?

You know, this was intense and very different from most episodes of Ray Donovan because the score really, really carried it and was right up front. Talking to David Hollander [writer/executive producer of Ray Donovan] it was something we knew we were going to do from the very beginning of the season. He told me that when we got to this episode, we were going to lean on the score to bring Ray’s state of mind to the foreground. It was almost like wall-to-wall music in a show that doesn’t do that very often. We were going for the sound of somebody who’s cornered and has run out of options. Now, he has to come out swinging and try to revert this situation, which is entirely of his own making to begin with. When he tells some of the cops they’ve captured early on that he’s not going to stop and he’s going to kill everybody until he gets his daughter back, that’s just Ray Donovan in a nutshell. The experience was challenging and fun — it was ultimately a very rewarding episode to work on.

We used some of the themes that already we had developed through the season, but I think a big part of it was figuring out how to do our version of an action score — something that propels you forward but still feels true to the show. Because no matter what it’s still Ray, and it’s still rooted in the reality and grit of New York City. One of the main things was making sure none of the instruments were too recognizable. We strived, in this season in particular, to make nothing sound familiar. Like the guitar-type instruments I mentioned, if you really listen, you realize they’re a lot more than just guitar sounds.

The interesting thing about working on a project like Ray Donovan is that by the time you get to the sixth season, the show really has its own sound. You chip away on every episode, trying something new, and the sound of the show expands, but because we’ve never had such a music-heavy episode in all of the seasons, we had to figure out how to score it in a Ray Donovan way. It’s almost like the show has become a living creature, and we — the filmmakers, David Hollander, the showrunner, the picture editors, my music editor, myself — define what kind of animal it is and understand that it behaves in a certain way. As a composer, you have a lot to do with the overall chemistry and what creates that animal to begin with, but there are still specific things that a show wants and doesn’t want, and they become more and more obvious as the show goes on.

As artists, we’re always trying to push the limits and uncover a new angle to the story that we haven’t seen before, but still respecting what it wants to be. A great director I’ve worked with used to tell me that if you listen carefully, a film will spit out of the music that it doesn’t want or need, and I’ve really taken that to heart — this was many years ago, and I still think that way. Once you put something against picture, it will tell you what it can or cannot take. Listening is everything, and for a composer, it’s crucial to pay attention to what’s coming at you from the screen.

The Romanoffs is a modern drama anthology which explores eight distinct stories of people who believe themselves to be related to the ill-fated Russian royal family. Matthew Weiner recruited you to score the Panorama episode, which is set in Mexico City. The plot follows Abel, a romantic gossip columnist, investigating a corrupt medical clinic, and Victoria, an American woman and a supposed Romanov descendant he falls in love with, whose twelve-year-old son is a patient there. Your Latin American and Spanish flavored musical atmosphere has a very sentimental, anachronistic quality. What were the core inspirations behind this score?

I’m a giant Matt Weiner fan, so when I had the chance to work with him, I jumped at the opportunity. What he did with The Romanoffs was a real undertaking. Writing and directing all eight episodes, and each of them is like a freestanding movie.

For Panorama, it was something of a love letter to Mexico City — that was the thing that really brought everything together. It was essential to Matt that there was a sort of travelog element to the show, where you go to all these different parts of Mexico when Abel decides to take Victoria to see the cathedral, the murals, and eventually, the City of the Gods. Through the eyes of the filmmaker, it’s Matt Weiner showing us this incredible city with such richness.

As you know, I’m Brazilian, not Mexican, but I’ve worked on many Latin American themed projects before. I think a couple of them influenced Matt Weiner’s decision to hire me — Sin Nombre, the first Cary Fukunaga movie, and Last Stop 174, directed by Bruno Barreto, who is Brazilian too. I think Matt wanted a composer who could bring a Latin quality to the story but did not want the music to sound purely Mexican. He wanted it to feel extremely romantic and almost of a different time, particularly in the moments having to do with Abel and Victoria. There’s also almost a caper, thriller element that you hear when Abel is sneaking into clinics and conducting his research, but it was important for the score not to sound too contemporary. Matt was very open to me using anything I wanted, so we ended up going with a lot of accordions, different types of guitar and flute, a string quartet to give it a timeless sound. It was a very satisfying project to work on.

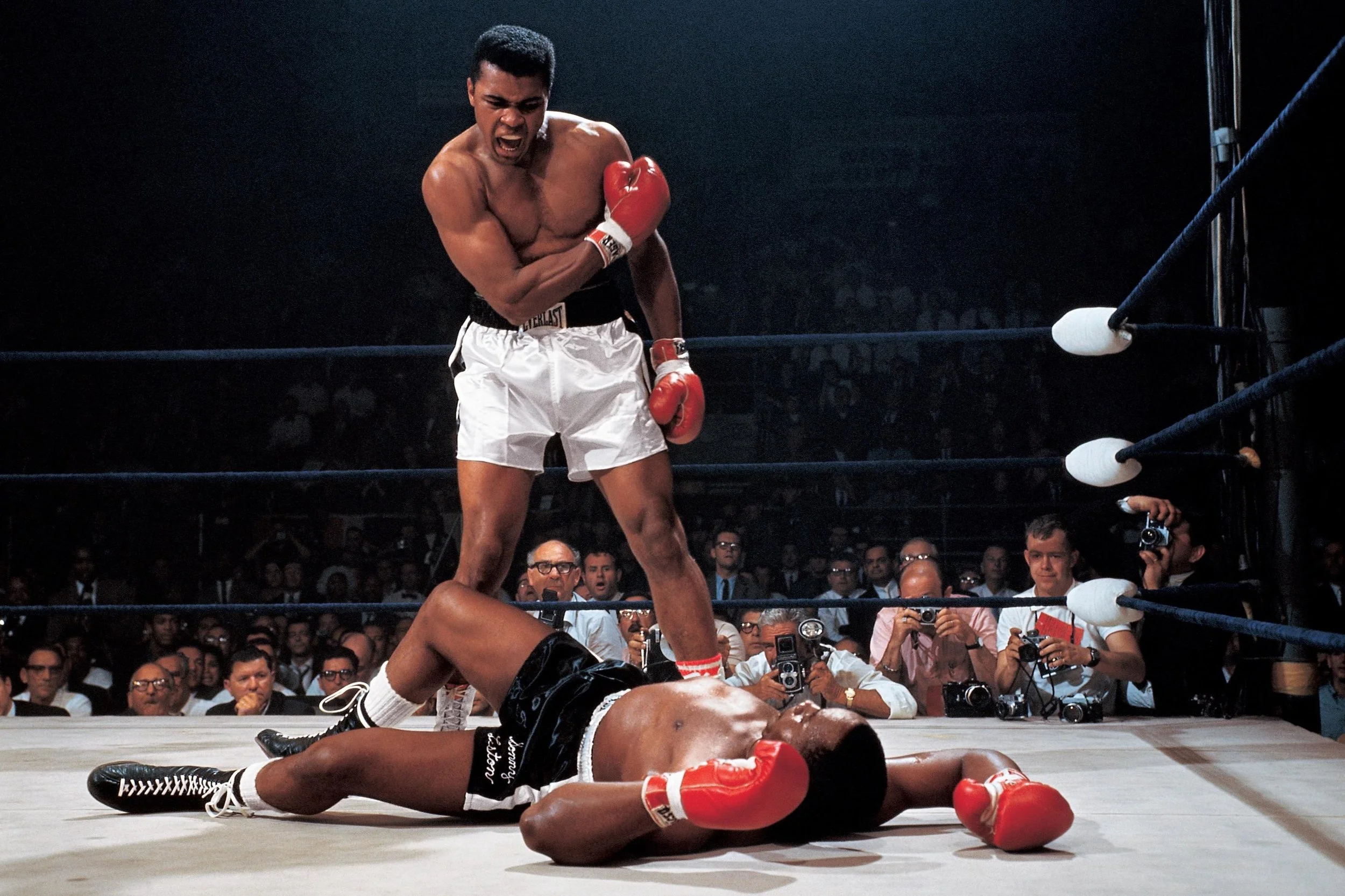

From LeBron James and Maverick Carter’s SpringHill Entertainment, What’s My Name: Muhammad Ali examines the legendary life story and career of world champion boxer and social activist, Muhammad Ali. The documentary is comprised of never-before-seen archival footage, which demanded a more robust and dominant score to communicate the heroic strength and cultural impact of Ali. Back in 2009, you previously worked with the director, Antoine Fuqua on Brooklyn’s Finest. Can you elaborate on how you decided upon this musical approach together?

As you mentioned, Antoine and I had worked together before on Brooklyn’s Finest, which was a great experience for me because I’ve been a huge fan of his from the very beginning — The Replacement Killers and of course, Training Day is possibly one of the greatest crime dramas ever made. When he called me to do Ali, I had no idea what to expect. I knew it was a documentary, but I didn’t know what the format would be.

The whole idea is that Ali would be telling his own story. One of the main things Antoine talked about was that we were portraying a hero and that the documentary was about his rise to become the world champion he was, and how he came back repeatedly to reclaim that title. Another important part was how he harnessed his power to leverage people to work for the civil rights movement. Those two things together were the heart of this story — the very thing that drives you to succeed and makes you great can also be the thing that might kill you in the end.

The film has two chapters. The first chapter is this long but very strong ascension to become a champion and a person that the whole world admired. The second chapter is him holding on to that because he literally needed the money from the purse of his fights to enable his work as a civil rights fighter. Ultimately, he didn’t know when to stop. He sacrificed himself to keep fighting the fight — in and out of the ring. Towards the end, by the time you get to the Leon Spinks fight, you feel so sad and horrified, now knowing what happens to all these boxers with brain damage. Despite all of that, Ali was a fighter in the deepest sense of the word and a real hero.

Like in a lot of classic stories, the hero dies in the end, sacrificing themselves for the greater good, and I believe that was the story that Antoine wanted to show, along with how Ali took on the government and spoke very loudly and explicitly about the treatment of African Americans in the United States.

What informed your palette to embody the spirit of Ali?

From the very beginning, Antoine wanted for the fights to be scored like action sequences in the movies. The most challenging of all those fights was the first Frazier fight that is almost a twelve-minute long montage. It’s nonstop music, and you have to know how to lead the audience into the drama of what’s going on because boxing is very psychological. A lot of it is in your mind; it’s about strategy — when to hold back and when to go for it. One critical element for Antoine was the clock — how fighters are not only fighting each other but also fighting against the clock. In the case of Ali, it was true in the sense that he was fighting through each round, and timing himself to be able to survive until the end of the match. In Ali’s life, he was also fighting against time itself and getting older, which happens to everybody. In the end, when he loses a big fight, he talks about how father time finally caught up to him.

It was a very heterogeneous score with styles ranging from jazz, to classical orchestral scoring, to just brutal percussive music for the fights. There is even some ’70s fun stuff in the middle of all of that. Antoine was keen on me exploring both the physical strength of Ali, but also his smarts and his quick brain. Antoine always talked about jazz, and how an improviser can come up with melodies in their head on the spot. He would also talk about what Miles Davis would sound like as a boxer in a metaphorical way, so we ended up incorporating all of those influences as well. We used a lot of jazz trumpet with all this percussion, electronic sounds, and the orchestral element to build up this real-life hero.

Based on real events, The Best of Enemies examines the dynamic between C.J. Ellis, a local Ku Klux Klan leader, and Ann Atwater, an ardent civil rights activist, who engage in a power struggle over the desegregation of schools in Durham, North Carolina in 1971. How did you negotiate this unusual juxtaposition of impassioned characters and competing social agendas in your score?

From the very beginning, I remember talking to Robin Bissell, the writer, and director of The Best of Enemies, and the main thing he wanted us to find was the common humanity in these characters. You have to believe that underneath the awful, horrific surface of a KKK leader that there is a human being in there. By just treating him like a monster right off the bat, there would be nowhere to go. Of course, he’s engaging in this monstrous activity of persecuting people because of their race and ethnicity, but he still has love for his family. So, it was about trying to find a way into this person’s heart, so later, when his big change of point of view comes about, and his character sees the light, it’s believable. We had to plant the seeds of humanity in this person, so that redemption, for somebody so deep in a very inhuman direction, would seem possible.

Even though the film is extremely dark, there’s a lot more implied darkness than actual violence you can see. A lot of the time, you don’t see the horror. You just kind of intuit what has happened or what is about to happen. Robin and I wanted to figure out a way to trace that slow and deliberate change of perspective he had because it’s the ultimate climax of the movie. I wanted to use a lot of steel guitar and a lot of plucked stringed instruments in a more folky way. We even used some banjo and some other things that are loosely related like hammered dulcimer and mandolin. We did use effects here and there, but a lot of it was trying to ground the music geographically in a rural area in the American South.

There were no fast rules in terms of needing to use certain kinds of instrumentation, but these sounds just felt right for the period and the place where the story was taking place. I’m a big fan of limiting my choices somehow because it can be very maddening as a composer when every color is available. It’s like, which ones do you pick? In this case, it felt very natural to me. We didn’t have a long schedule, but we had enough time to be able to calmly and deliberately write a score which became very organic to the movie. This one was a very smooth process, and it was just great.

Based on Laura Moriarty’s New York Times bestseller, The Chaperone is set in the 1920s and follows a rebellious teenager, Louise Brooks, who travels from her native Kansas to the Denishawn School in New York City to study dance for the summer. Along for the adventure is Norma Carlisle, a stern society matron with opposing values. From your perspective, what themes in this narrative inspired you to sculpt such a lush, sweeping sonic statement? What are the primary considerations when you approach a period piece feature?

There were some things in The Chaperone that were determined ahead of time. In terms of palette, we decided that all of the jazz would be left to the source music — all the needle drops would take care of that speakeasy sound. In terms of score, there was certainly a lot of it, and it’s very, very present in the movie. The inspiration came from the pieces that Louise would dance to, so there are a few classical pieces that they use in the studios — Debussy, Liszt, and Schumann.

When I talked to the director, Mike Engler, he wanted me to think of those pieces as inspirations, not in the sense of getting ideas for themes from them or anything like that, but just to consider the way they work. Those happen to be composers I love, particularly Debussy, and they’re all very piano-centric composers that I studied and performed before, so it was a lot of fun to use that as an initial place to begin. In terms of the sound, we wanted the score not exactly to have the sound of New York per se, but capture the sound of New York through the eyes of these two women.

One of the things that really appealed to me was the basic premise of the story. The writer of this movie is Julian Fellowes, the creator of Downton Abbey, which is a series that shows history through the eyes of characters that exist in the background. In Downton Abbey, you have all the help that lived downstairs and so forth, but I’ve always felt that scores are kind of like the chaperones of movies. They are not always in the front, but they influence what happens. I think composers tend to be very comfortable with this idea of being behind the curtain, manipulating emotion with sound. So, I love the idea that you’re seeing a coming of age story that at first seems like it’s going to be about Louise Brooks, but actually ends up being a coming of age story for Norma Carlisle, the chaperone. In the end, she is the one who is liberated.

It was important to Michael Engler for the music to fit the size of the story. Sometimes it’s tempting to go as big as possible in movies, but there’s this strange thing that happens when the score is too big for a scene, it makes the film feel smaller, and we were very aware of that. It was intentional to make the music more chamber-like. Even if there are more sweeping parts, it was always within a chamber approach. Ultimately, this is a story of two women, and a lot of it takes place in small spaces when they are talking and living their lives.

We had a string quartet, woodwinds, harp, piano, and a little bit of trumpet here and there, but we knew it needed to be intimate and always capture the sense of awe they felt in going to New York. I know I still feel that way when I go to New York, where the city is so electric, but imagine what it would be like for somebody traveling there from Kansas in the ’20s. That’s like, whoa! There was a rush of excitement in both characters for different reasons. One is just starting her life, and the other is about to start a new chapter in her life without really knowing it. This story was really about highlighting the connection of these two women and how they help each other transcend who they are at the beginning of the film.

Agreed. A lot of people seem to think that the more instruments you have, the bigger something is going to sound, but in most cases, that’s a misconception, and it actually feels less impactful.

It’s true. You know, I’m a big advocate of ‘less is more’ especially when it comes to film and TV scoring because you really have to find the right way to approach the picture. If we circle back to a project like [What’s My Name: Muhammad Ali] when he’s fighting, the percussion needs to be big and brutal, but in the case of The Chaperone, these are delicate characters. They’re very resilient inside, but at that time in history, women were kept very locked away in a sense. When they come to the city on their own, there is such an incredible sense of discovery. Norma, in particular, is searching to find herself outside of her marriage, outside of her family. These qualities felt better supported by a small chamber-like group, so once we found that size worked well, we didn’t deviate from it very much because it felt so true to the story we were telling.

Next up, you’ll be taking a turn into the land of comedy for Cindy Chupack’s Otherhood, which is based on William Sutcliffe’s book about three suburban mothers who visit the homes of their sons living in New York City unannounced. Is there anything you can share with us about this forthcoming score?

Yes, we finished it already. Otherhood is a story that celebrates motherhood and family. It’s also about mothers trying to fix their kids’ lives even when they don’t need fixing, and creating havoc with good intentions. All their kids are grown ups starting their lives in New York, all equally mortified for their mothers to show up without invitation, and of course, things don’t go as planned. The three lead actresses are Patricia Arquette, Angela Bassett, and Felicity Huffman. They’re all amazing. It’s incredible to see such top-notch acting within a romantic comedy.

Cindy Chupack is such a phenomenal writer, who did some of the great Sex in the City episodes, and there was just a very talented group of filmmakers involved. The score is very fun and kind of comedic. It’s orchestral, but it has a lot of guitar and percussion. I would say it’s a contemporary sounding score with a lot of heart. It’s a very beautiful family story.

Are there any other exciting projects of yours we can look forward to in the coming year?

I’m working on a really cool seven-part series now called The Loudest Voice. It’s a biopic about Roger Ailes of Fox News, which comes out on June 30th on Showtime. It really shows off the paranoid right-wing mentality. Roger was one of the people that harnessed that fear the most. You know, most people can trace Trump’s ascension directly to Roger Ailes because he really put his muscle behind him. The series jumps around a span of twenty years of his life.

Russell Crowe portrays him brilliantly and is completely unrecognizable. Roger Ailes was bald and very overweight, quite a bit different than Gladiator, [laughs] but it is very convincing. It’s a really great show.

It sounds like we need to bring Muhammad Ali back to speak on this present administration.

Absolutely! We need all the help we can get, and all the heroes we can get. It’s a crazy time in the whole world, not just here in America. In Brazil, they just elected a super right-wing president. All over the world, there is so much anger and people are turning to the right. It’s so confusing, but having learned a little bit more about Roger Ailes and where he is coming from, they really look at it like they are catering to the people. There’s a great quote from him; he says, “People don’t want to be informed. They want to feel informed.” A lot of it is about preaching to the converted and people just being at each other’s throats.

Hopefully, the Beatles lovers of the world can unite to make the world a better place.

Absolutely. Hopefully, love will conquer all. We have to believe it. There’s no other choice.

Interviewer | Paul Goldowitz

Research, Editing, Copy, Layout | Ruby Gartenberg

Extending gratitude to Marcelo Zarvos and Jeff Sanderson of Chasen & Co.